Max Yasgur’s Farm

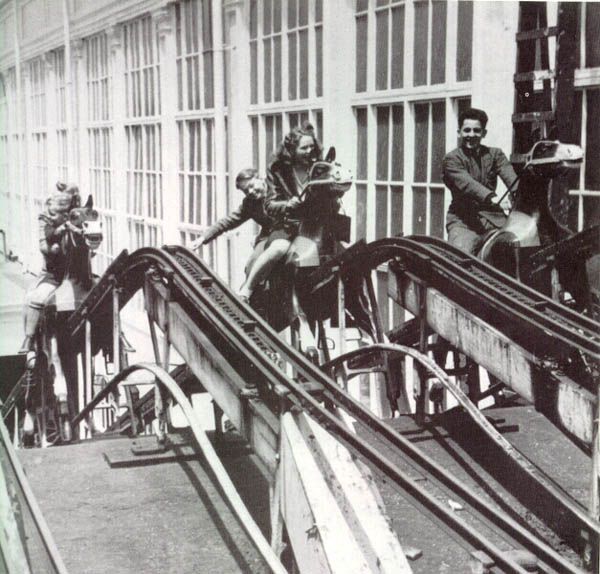

After a years-long blogging sabbatical, about ten days ago I posted an article that was inspired by a report of a Florida boy falling out of a roller coaster. (It has since been reported that he’s home from the hospital and recovering.)

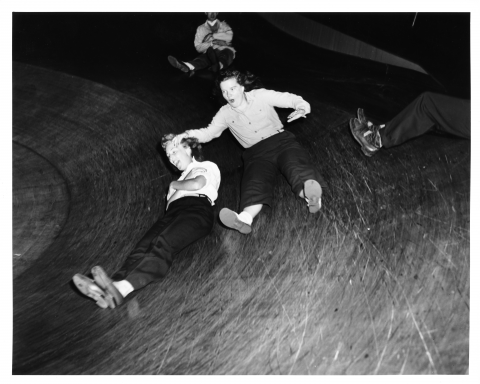

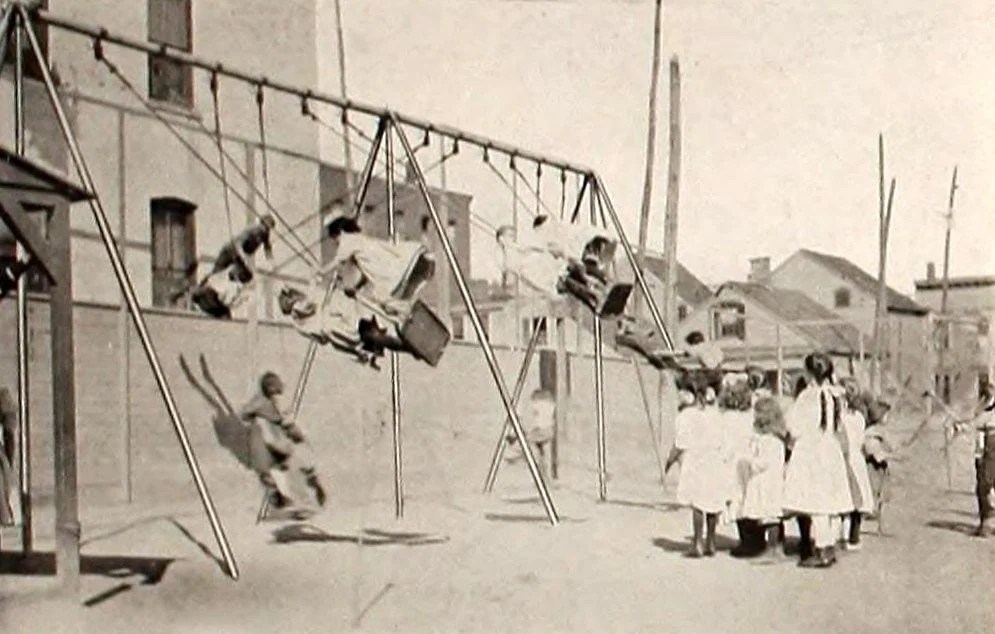

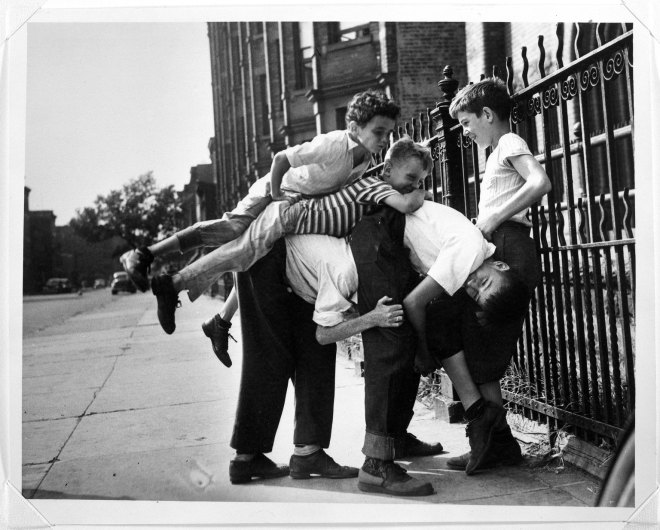

That incident brought to mind how dangerous amusement park rides were when I was a kid, which further reminded me of how dangerous school playground equipment was back then (Fifties and Sixties). The resultant blog has pictures of a seesaw, monkey bars, swings, and significantly, steel slides and a merry-go-round.

You can read it by clicking on the post to the right entitled Wing (Winganhauppauge) School-Playground, Islip, NY

Within days of posting, I traveled to Bethel, NY, which is where the original Woodstock Music festival took place in 1969. Beginning in 1994, I started visiting Bethel where reunions of various sizes had been taking place nearly every year.

In the very beginning, they were held on the original festival site (without the owner’s permission), which was a nondescript and mostly forgotten cow pasture. Through the seventies and eighties hardly anyone came, but the 20th anniversary in 1989 sparked renewed interest in Woodstock.

More people came in the early nineties, and in 1994, a big 25th anniversary was scheduled for the original site. Though the formal concert was cancelled at the last minute, thousands of people came anyway, and a pretty big rock show was staged (on six flatbed semi-trailers).

In 1996, a recently minted cable TV billionaire named Alan Gerry (pronounce G like Gary), bought the property and declared the site off-limits. With no place for Woodstock celebrants to go, local businessman, Roy Howard, and his wife Jeryl, offered to allow the newly displaced revelers to camp on their Yasgur Road property.

That was nice of them, and over the years, The Farm became the place to go in Bethel to celebrate the anniversary. Of note: The Farm is where Max Yasgur lived when he agreed to let the original 1969 Woodstock promoters use a section of his property for the festival (the festival site is about two miles from Max’s modest house, which is still there).

Some years the celebrations at The Farm were large, maybe a couple of thousand people. Others were small, maybe a hundred or so. Whatever their size, Roy and Jeryl dealt with lots of municipal permit and code issues that were unpleasant and costly.

When I go, I camp there. I am familiar with the property, but very soon after I arrived this year, I noticed something: Two Merry-go-rounds (one working, one not) and a steel Slide, both of which are very close in design to those shown in my recent blog.

This equipment has been on the property for a while, so I’ve seen it before. Still, it seemed significant that within days of writing about long-forgotten playground apparatus, I found myself camped right alongside it. I took some photos of the equipment.

A skeptic might say I wrote about the merry-go-round and slide because I knew I’d be going to Bethel and they somehow rose from my subconscious. I don’t think so. It was the kid falling off the rollercoaster that prompted the post and recollections, so I’m chalking this one up to a very good example of Synchronicity.

Here’s another: WFDU, Daddy Dew Drop, and Chick-a-boom

During the very first week after my visit to Bethel, another odd coincidence occurred. It has nothing to do with Woodstock but makes a musical connection.

In New Jersey there’s a local radio station that is affiliated with Fairleigh Dickenson University. Its call letters are WFDU (listen on the internet: wfdu.fm), and they play a lot of obscure pop songs from the fifties, sixties and seventies. On my first Tuesday back from Bethel, WFDU played a 1971 song called Chick-A-Boom (Don’t Ya Jes’ Love It), by a guy who at the time called himself Daddy Dew Drop.

His real name is Richard “Dick” Monda, who started out as an actor and became a songwriter, performer and music producer. A photo of Mr. Monda if to the right:

I remembered the song as soon as it came on. It was a massive hit in 1971, reaching number nine on Billboard’s national chart. The song was originally written (by Gwin and Martin) for a television show called “Groovie Goolies,” a program for which Monda had produced music.

I’m not sure if the song ever made it onto the show, but Monda rewrote the lyrics and recorded it with studio musicians. At the time, the story it tells was considered risqué. It recounts a dream where the protagonist follows a girl in a black bikini, who along the way removes parts of it, first the top, then the bottom.

He goes around corners and into rooms, finds himself at a party and comes upon early Rock ‘n’ Roll icon “Little Richard,” (deduced to be him because the lyric reads: “this really far out cat was screaming half-crazy: A-bop-bop-a-loom-op-a-lop-bop-boom,” which is from Richard’s signature song: Tutti Frutti). It might’ve been just some far out cat screaming Little Richard’s catchphrase, but people who comment on such things have assumed it’s Little Richard. Here’s the Chick-A-Boom song:

Daddy Dewdrop’s delivery reminds me of Dr. John, kind of a cool Louisiana drawl, though Monda was from Ohio and grew up in California. It also reminds me a little of Sam the Sham (of Wooly Bully fame, out in 1965) and Tony Joe White (Polk Salad Annie, from 1970, which is such a cool song). Some other internet commenter said Chick-A-Boom reminded him of Eric Burden, and it’s hard to miss the similarities between it and Burden’s “Spill the Wine,” from 1970.

Prior to last Tuesday, I don’t think I’ve thought about the Chick-A-Boom song in at least forty years. Not at all. Not once. The reason songs fade into obscurity is they stop getting played after their time in the sun. That’s what happed to Chick-A-Boom. There’s no explaining why some songs stay in the “oldies” rotation, and others don’t (but it did make it onto the “One Hit Wonders” wall at the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of fame.)

A few days after hearing the song, I was at the local Stop and Shop picking up a few things—you know, dinner and stuff. Anyway, I had an urge for popcorn and went to the snack aisle. I am a careful shopper and am always looking for a bargain (as my mother used to say).

The price of snack foods (potato chips, pretzels, corn puffs, corn chips and popcorn) have really gone up lately, and I was scanning the shelves for reasonably priced popcorn. I couldn’t find any. The cheapest was on sale for a little under $4.00, but I figured what the hell, you only live once, and threw a bag into my shopping cart. Here’s a picture of it:

Granted, it would be a more amazing coincidence if the popcorn was called Chick-A-Boom, but damn it, “Boom Chicka Pop” is close enough to put it squarely in the Synchronicity category.

A skeptic might say that the Chick-A-Boom song was floating around in my subconscious and that was what drove me to buy the Boom Chicka Pop brand. I would say I bought it because of its low price, but who the hell knows when it comes to subliminal motivations which nobody really understands. After all, the brain is a pretty complex and mysterious thing.

But still, it seems the universe is sending messages. If only it would include next week’s lottery numbers.

Until next time patient reader, adieu.